48″x60″ – Oil on wood

I’ve spent a good bit of time breaking down the components of painting in order to become more thoughtful about my work and to help others do the same. To my way of thinking, the intent of the work is the number one consideration in any creative endeavor with the narrative/story next in importance. Yes, drawing, color, shape and all of the aspects of craft are critical for the realist painter but once that skill set is acquired, what do you do with it?

Every song has a narrative, every movie a storyline, every poem a scenario, each novel a plot, every song an emotion, and every picture tells a story. Why should a painting be any different? The intangible thing that separates the greats from the pretty-goods is rooted in a deep pool of ethos that is mixed into every puddle of color and imbued in every movement of the brush. It’s the foundational idea of a piece that sets the tone for a poignant outcome.

You may be thinking that I’m referring to the Golden era illustrators or the cowboy and Indian paintings that fill every gallery in the west. I’m not, but that’s as good a place to start as any. A quick Google search of “golden era illustration” will give you a balcony seat view of some of the greatest storytellers of the last century; Mead Schaeffer, Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, Dean Cornwell, Jessie Willcox Smith, the list is incredibly long. This, one of the most prolific movements in the narrative arts, housed the masters of story, design, style, and ability.

30″x30″ – Oil on canvas

One of the tricks (beyond a brilliant design) to creating a powerful narrative in a painting is to think like a movie director. After all, a painting is a single-frame movie that speaks to a moment in time, but the outstanding ones hint at the preceding events and those that are yet to come. If you incorporate a figure or figures in your work, you should know them as a writer knows his/her characters. What are they thinking? What is their backstory? Why are they there? What do their expressions, posture, and the placement of the hands, say about them?

Go through a top 100 movie frame by frame, Citizen Kane or The Grand Budapest Hotel come to mind, and look at the construction of each scene. What symbolism does it hold? How is it designed? What are they up to and what’s coming next? That’ll fill your noggin with some new ideas.

I appreciate the skill in a great portrait or a well-executed nude but I, as a viewer, want more. If you’re going to paint a beautiful female nude languishing on a sun-drenched bed, put an easter egg in there to give the discerning eye something to think about, something that hints of events beyond the boundaries of the frame. The viewer wants to be included, let them fill in some of the script. Think like a writer, give them enough but leave room for the imagination. Tap into your inner recesses and tell your story.

48″x48″ – Oil on wood

A painting doesn’t have to contain pirates or a well-heeled couple in high society to communicate a message. Even a simple still life should hint at a plot line. Who put the stuff on the table? What are the flowers feeling? What’s the relationship between the asparagus and the knife and who drank half the beer placed at a calculated distance from that nibbled on bread? The space between objects is like a pregnant pause in a conversation. It helps to create a compelling plot even if the characters in the play are just vegetables and dinnerware. Assign human characteristics to every piece in your static production. Use your friends and family as a reference for a more compelling dysfunctional still life.

If it’s a landscape, there’s always a story to tell. What is it about this place that you are painting that is important? Who lived there? Or died there? What would a pioneer have felt having seen this place for the first time? What would Thoreau say about this land? How does it feel on your skin? What memory does it spark? What is the message you want to convey about that bustling street scene? Even if it just stays in your head while you are painting, it may not be readily evident, but the lookers-on will feel it.

48″x60″ – Oil on wood

So, how does it make you feel? If you took 15 minutes before you ever lay brush to the surface to write about your sense of place you’d have a deeper understanding of what you are saying to the viewer because you have defined it for yourself. Your palette, your brushwork, drawing, design, and style all go to the story. Every mark and movement should be in support of the plot line.

Included are a few of my own pieces to show how I weave the narrative into a body of work. It took me a while to find it. The broad theme is that of environmental concern, but each piece has its own sub-plot. Sometimes the story is written before I begin and other times it unfolds as I go. I’ve come to view this series as stories that I tell myself. If other people get them, all the better. More often than not they make up their own. But, at least, I am telling my story.

Education

OPA Buyers and Collectors

I recently wrote a blog titled ‘So You Want To Host A Plein Air Event,’ in which I identified the three required components of a successful event: Artists, Organizers, and Buyers. Similar to a three-legged-stools, without one of these components the stool falls over. Of the three, Buyers/Collectors is the one most often neglected. Attracting buyers and developing collectors takes a little more effort; takes a little education, not unlike developing a taste for fine wine or cigars.

Wes Heitzman, a good friend and one of the key organizers of the amazingly successful Bluff Strokes Plein Air Event in Dubuque, IA, wrote an insightful article from the point of view of a Collector. I think this article will go a long way towards that education and have an eye-opening impact on Organizers, Artists, and future Art Owners alike.

I bought my first piece of art from Steve Steininger, at Dubuque Senior High, during our graduating year of 1967. Senior had a great art department and some excellent student artists, and my mother had advised me that a good way to start an art collection would be to buy from student artist friends. “Me Bird” is a woodcut in red and brown tones. It is a quirky depiction of a man wearing what first appears to be a large helmet, but on further inspection is a large mass of feathers. Looking very closely, 3 faces of birds reveal themselves hidden among the feathers. I loved this work for its cleverness, its skill of execution, and that it was the creation of a good friend. I still remember my teenage pride when I picked it up from the frame shop in a professional-looking wooden frame with high quality, non-reflective glass. “Me Bird” has accompanied me for 50 years, gracing dorm room walls, and then living rooms, bedrooms, and dens of various abodes through my life. Today, in my home office, it still elicits fond remembrances and a smile.

I will come back to “Me Bird” in a bit, but here are a few reasons to favor your home with original art. First, just like you, an original work of art is unique – there are no other versions out there, you will not walk into a friend’s house and see an identical copy, it will be an extension of your unique personality. Second, an artist producing original works uses better materials than are used in reproductions. Look closely at a pastel, oil, or watercolor painting – at the layering, the texture, the interaction with the underlying paper or canvas; a reproduction will use cheaper inks and paper and will appear flatter than a work of fine art. And yes, you will respond to this differently on your wall. The same goes for a handcrafted pot vs a manufactured one; and though I love pottery, I’ll focus here on things you can hang. A third consideration is value.

In general, a unique work will hold some level of value, and possibly a chance of significant gain, whereas a mass produced work will have little to no resale value. It can be rewarding to find individual works or to create a collection with investment value. This requires research, strategy, and networking into a world of professional dealers; but I would like to focus here on adding value to our lives.

A work of art is a conversation; an expression of an experience an artist is having with the world. When you bring a piece of art into your life, you participate in that conversation. Roy Haught was an art teacher and also a hunter, camper, and outdoorsman. His work explores and reflects those interests. I have a watercolor of Roy’s that depicts a row of conifers along the crest of a hill. For years, I drove by a similar row of trees on the way to work in Waterloo. After we hung Roy’s painting in our home, I started seeing those trees when I drove by. We have a small painting by Ellen Wagener of a pale pastel blue sky above a very low horizon. I once was driving in western Iowa to the funeral of an aunt, looked out over the fields, and saw that sky – because of Ellen’s directing my perception. These experiences were profound. I have many times watched my wife, Barbara, a pastel artist, go into a “zone” as she explores a still life or landscape and translates it to her media. This experience is shared by artists everywhere as they converse with their world. When you buy an original artwork for your home you are sharing in their experience and their conversation.

Recent research in neuroscience suggests we have two “systems” of thinking. System 1 works in background, monitoring the world, capturing impressions, checking for strange or threatening events, and throwing out intuitive judgments and responses. System 2 is engaged when analysis or self-control are needed. This research has transformed economic decision theory; but relevant to how we relate to art is what it has revealed in how we store and retrieve memories. System 1 maintains a vast system of associative memory. When we encounter a word or image, a ripple of associated ideas, images, and memories is evoked without us even being aware. These influence and bend our current thoughts. If you are asked to fill in the blank letters in “S _ _ P” you are likely to write SOUP if you have recently been discussing cooking, SOAP if cleaning. Words and images you encounter even affect your moods and behaviors; you will walk slower and stoop a little more if you have been discussing aging than if you have been talking about running. All of this means that when you look at a work of art in your home, a flood of associated memories will enter your mind, affecting your thoughts and your mood without your even being aware.

With that in mind, the act of purchasing an original art is often a personal adventure. We purchase in interesting galleries, at art fairs and special openings, sometimes even in an artist’s own studio. We may meet the artist, glimpse how she sees the world, see something a little differently through her eyes. All of this is evoked in your associative memory every time you look up and see your artwork. Art you put in your home will continue to enrich your life in a way that mass-produced art from IKEA or Pottery Barn cannot.

“Me Bird” has continued to provide a smile in my life and has been joined by many other pieces. Each carries its own history and memories. Each has added joy and richness to my life. I recently talked to a young friend, Jennifer, who had just bought her first piece of original art. “Cleo” is a large colored pencil drawing of a hog she and her husband Aaron commissioned from Hana Tysver Velde. It now hangs in their living room over their couch. Jennifer’s comments: “We love it because it’s beautiful and well done and it’s unique – no one else has it. It also has meaning. For Aaron, it symbolizes his family heritage growing up on a hog farm, and for me, it doubles as a symbol of our life together in Iowa.” I asked Jennifer how it felt to have a piece of original art in her home. “Pretty friggin cool!

Some notes on getting started collecting. I have noticed that one of the biggest impediments people wanting to buy art is self-doubt. They don’t think they have an eye for quality. They don’t know what is a fair price. A little self-education will build confidence. Here are some thoughts to get started:

- Learn about the arts community in your town/city. What artists are working around you, what are the area art events, what galleries are in the area? Extend this out to neighboring communities within easy travel distance.

- Get familiar. Walk into galleries and studios, browse, and note what really pops out at you. Ask about the artists, where they are from, what is interesting about them.

- Attend art openings. Meet some of the artists and get to know their work. You also get free snacks!

- Go to art fairs and festivals, plein air events. Artists sell their work direct in a fun outdoor market environment. Talk to them!

- From all of these interactions, develop a feeling of what you like and dislike. Take a chance, buy a piece, hang it, and ask yourself what distinguishes it from that Pottery Barn reproduction.

- Look for opportunities to buy art within your budget. For us, many Christmas gifts have been artworks that we gave each other as a joint gift.

Artistry and Craftsmanship

You enter an art museum… you come around a corner… and there it is: a painting that immediately draws you in. Somehow through mere paint on a canvas it speaks, stirring your soul, even though the painting was painted long ago. Amazing isn’t it? This happened to me. I came around the corner to see Lady Agnew by John Singer Sargent at the Edinburgh Museum in Scotland. I couldn’t stop looking at her while admiring Sargent’s mastery.

by John Singer Sargent

As representational artists, we aspire to grow in the mastery of our own work. In this article, I will discuss how Craftsmanship will advance our Artistry.

Artistry

A masterfully painted artwork speaks with eloquence without a single word. This quality of art has the ability to communicate the human experience across language barriers. Master artists like Sargent have developed a sensitivity and ability to observe what they see and faithfully express even the emotion of the person they are painting.

How do accomplished painters achieve their artistry? Is it just exceptional talent? Certainly, each accomplished artist has a unique talent, an innate gifting. For that gifting to be realized other qualities come into play. When an innate gifting is paired with a desire and dedication to excel in the necessary skills, true artistry pours from the work. Before artistry emerges, craftsmanship paves the way.

Craftsmanship

Craftsmanship is foundational skills aspiring artists need to produce strong, convincing works of art. As a visual artist you need skills that train your eye to see and with practice to reproduce what you see.

Four Foundational Skills to Create Strong Works of Art

- Drawing/Shapes: accurate placement and proportion.

- Values of Light and Dark

- Edges from sharp to lost

- Color: warm and cool, as well as hue, value, and saturation.

By mastering foundational skills until they become second nature, we gain freedom of expression, for our aspirations to soar.

How do you find your artist voice? A few thoughts:

- Practice with sensitivity as you are learning and perfecting your craft, the artistry needs to be there each step of the way.

- Look around, as you go about your daily life. See beauty in common things, the color of distant mountains or the smile in the eyes of a child.

- Observe light through the day, whether it is a rising sun casting long shadows or a light shining on a loved one.

- Be inspired through the other arts. Go to concerts. Listen to music that moves your soul as you paint.

- Paint from life. It is challenging and why we need those foundational skills. Here is a quote from my blog:

“At the studio that I paint at, we all show up, set up our easels and supplies. The model is set up in his/her pose. A flood of activity is taking place. Then suddenly the light goes on, the timer is set, and all is silent as we take in what we see and formulate our next steps. I feel blessed to have the privilege of standing before a living human being to paint him/ her. The beauty of the colors of light on the skin, warm and cool tones cascading over their form is something that doesn’t show up with such nuance and subtlety in a mere photo. Beyond the imagery is the personhood of the model that seems to emanate into the room. How do I capture it all with mere paint on a blank canvas? There is our challenge – to communicate life and beauty to our viewers.

Each of the two paintings pictured below were informed by a life painting experience. Even though they were both started on fresh canvas at home, using a photo; the memory of each experience was strong in my mind, especially the temperatures of the light. In both works, I hoped to capture the expression of the model, especially Moon Dance. Read more below.

“There was something compelling about her gaze that immediately drew me in. She had a delicacy and captivating fragility about her. As I looked into her face, particularly her eyes I felt as though I was drawn into her soul. My hope was to go beyond the mere image to capture her delicate expression in those moments while they were still fresh in my mind. ”

Aspiring to be an artist is a lifelong passion where you never fully arrive at perfection. There is always something new right around the corner to move you closer to your vision. We are each on our own path growing as fellow companions in our quest. We are never quite finished.

Painting is an expression of life.

BACK TO BASICS: COLOR

In a fall post last year, I spoke about the importance of value in the hierarchy of a painting’s success. Color was the third item listed:

1. Drawing

2. Value

3. COLOR

4. Edges

In this post I’ll briefly share a few thoughts on color. Before anything gets discussed about color, let me give two caveats:

1. Though color delights and has huge emotional impact, it really is the frosting on the cake; value and drawing are the cake itself. Far too many people jump into color without a proper foundation.

2. There are as many ways to do color as there are people. There’s not one right way. There are a lot of ways to do it wrong, but while some prefer strong color, others tend towards muted. Both (and a lot in between) can be right.

There isn’t time in a blogpost to cover all of the basics of color, and no one wants to read pages of color blather anyway, so the following are a random smattering of thoughts on color that have made sense to me over time. They are in no particular order of importance, and are not absolutes:

• Find the dominant value shapes in a composition, and then look for the subtle changes of temperature within those shapes. Almost never does a plane not have a subtle temperature shift of some type (sorry for the double-negative). Look at a white wall sometime: it will be warmer with bounce-light towards the bottom, cooler towards the sky, really blue at the base where weeds or bushes block the bounce-light, etc. These subtle shifts are what give things life and reality.

• Color really is all about context, about what a color is next to. For example, sometimes making something feel more red is about making everything else less red, rather than trying to add more saturation.

• Limits help color harmony. More colors on a palette doesn’t equal better color in a painting.

• Blue is the coolest color, and orange (blue’s complement) is the warmest. The warmer a scene needs to be, the more it shifts to orange, not yellow or red.

• Mix a light violet (Ult./Aliz/White) and use it to turn forms as opposed to using gray (b/w) (I learned this from Lipking). This is dependent on light conditions of course. The idea is to basically use the sky color (the indirect fill light, not the direct light) to turn planes away from the light.

• Mixing a little bit of each of the primaries in each mixture will give things more naturalism and harmony (not in equal proportions, obviously). This isn’t always true, but surprisingly often it is.

• Nature has a lot more red in it than we think.

• Deep shadows are almost always warm. (i.e. the holes in rocks, the deepest parts of tree shadows, etc).

• Humans are mostly very warm objects covered with a translucent cool colored skin. The earth is that way too — a giant mineral ball with a scattering of cool colored plants. Thus the warmth is going to show through in the gaps.

• To subdue greens, use red or drag some pink subtly over the top.

• Use complements to control saturation (i.e. cut a green with a red, orange with blue, etc)

• For stronger color harmony, decide on a dominant color and mix it into everything. The choice of dominant color is based on the overall light temperature for the chosen time of day + the emotional mood I want to convey. For example, in a dusk scene perhaps I’ll mix in a little bluegreen with everything but desaturate it to be more emotionally subdued (see attached example).

• Use juxtaposed temperatures to give things excitement (i.e. color charm). I’ll often paint a base layer warmer, for example, and then drag slightly cooler paint over the top (after the base layer has dried).

• One color can be a strong accent, but not two, generally (or else they compete). For example, if the barn is red and you want to push that, don’t make the grass and sky the same strong saturation, or it will be too much. Again, choose the main actor and then everything else sings harmony to that.

• Mixing up piles of paint helps prevent the inevitable thinning down of already weak mixtures. Doing so ends up giving muddy color because we are often too lazy to mix up more and thus keep adding more thinner to stretch it.

• The strongest color is generally found in the mid-tone/transition– i.e. where a shadow turns into light. Pushing color transitions allows for more muted color in the light while increasing the feeling of brightness/intensity. This isn’t just a trick, it happens all the time in nature.

• Generally, on location, I need to add 10-20% more saturation so that it reads correctly once indoors (where it isn’t being blasted by natural light). Otherwise my paintings tend to feel dead once inside. This also helps me to have a clearer idea of what I saw once using it for reference later on.

• When confused about a color on location, just do a little ‘finger wedge’ to isolate it and break it down into the three basic components of Hue, Value, and Saturation and trust what you see. Some people use a cardboard or plastic viewfinder for this. I tend to lose those things so I just use my fingers.

• And finally, if you’ve read down this far, I’ll give you the real secret to improving color sense quickly: MASTER COPIES. When I give this assignment to students, I have them do the first few by printing out a physical photo of the painting they want to copy, and then dab bits of paint on it as they are doing the copy to exactly match the color. This trains the eye to get over preconceptions about color and usually helps them realize just how much red is in the environment and how muted most of nature really is. Sometimes I’ll do these in oil or gouache (or even in three-value grayscale), but it really is one of the only ways I know to try on someone else’s color sense and understand new ways of seeing. Do them small, do them quickly (set a timer), and do a lot of them.

Happy Painting!

Confessions of an Unartistic Father-In-Law

My son-in-law is Jason Sacran. That simple fact constitutes my one and only real connection to the art world. What follows are the confessions of a man who has had art thrust upon him, and has lived to tell about it.

My son-in-law is Jason Sacran. That simple fact constitutes my one and only real connection to the art world. What follows are the confessions of a man who has had art thrust upon him, and has lived to tell about it.

I am not an artist. I confess that right out of the gate. In fact, if you were to do a nationwide search to locate the individual who was least like a graphic artist, I might be your man. Drawing stick figures taxes my ability to the limit. So, when an aspiring young painter suddenly joined our family circle, I knew that I was going to have to enlarge the scope of my knowledge if I was to be able to carry on anything approaching an intelligent conversation with him about his field of endeavor.

I did know a few names, so I dropped them occasionally: Picasso, Rembrandt, American Gothic. I knew just enough to ask questions to make it sound like I knew more than I did: “Who do you think was the greatest of the Impressionist painters?” (I was fairly sure that Impressionist was a type of art and not the name of an artist, so I took the chance and tossed it into the conversation.) The problem with such opening lines is that after the line was opened, my expertise was closed. I was at a blank wall and could go no further. So . . . I determined that I needed to further my education in art.

At this point we need to drop back in time and fill in the background just a little bit. I live in rural west-central Arkansas, about an hour east of Fort Smith, the second-largest city in the state. Saying that this area is not exactly a hot-bed of artistic sentiment is one of the more profound statements I will ever make. If you have an interest in deer hunting, football and pick-up trucks, you could hardly come to a better place; but if you mention that you are a painter you are likely to be asked what you would charge to put a fresh coat on someone’s front porch. (In this area the correct pronunciation of wash is “worsh,” and ought is “ort.”) I am happy to say that my own family does have some artistic talent. My younger brother is a commercial artist and his daughter is amazingly talented in the field of ink drawings. However, my background and that of my parents is in music, and we did not venture at all into the graphic end of the art world. I taught school for a couple of years, decided I was not any good at it, and ended up working in the office at a corrugated box plant for 26 years. (Boxes do have flutes and flutes are shipped in boxes, but that is about as close as they get to the art world.)

I have six children: two boys, and then four girls. So, I have had The Conversation four times – the one about marrying my daughter. There was one question that I asked all four of the young men regarding the material support of my daughters: “Would you be willing to work a double shift at McDonald’s if that is what it took to keep food on the table?” All four answered in the affirmative, and I have to give them credit that they all are hard workers who have given me no concerns in that regard. However, if I had known then what I know now about the life of an artist, I might just have probed a little further.

You see, Jason and Rebekah got off to a very rough start. Leah, my third daughter (fifth child) got married in August, and right about then Rebekah announced that she was going to get married that November. I answered, “Oh, no you are not! not if you expect me to pay for it. Your mother just got through with a wedding, and she has all the holidays folderol just ahead, and she is having to help take care of your grandmother. You put it off at least until after the first of the year so she can catch her breath.” She relented and moved it out to January 8th.

It was cold on the day of the wedding, we had all that wedding pageantry right on the heels of the holidays, with Jason’s family coming in from Tennessee; and on top of it all, Jason got sick. I mean sick! (I will spare you the medical details.) He did not even attend the rehearsal. He was white as a sheet during the wedding. We had to tell him what he was supposed to do in the ceremony, and he could barely stand. They were going to stay at the Peabody Hotel in Memphis, and Jason was too sick to drive. Then they had a flat tire right about the intersection of Interstates 30 and 40 in North Little Rock. Jason could not change the tire because he had taken some medicine to help with his nausea and was completely out of it. We called someone we knew in the area to come help them.

Soon the children started arriving. Their first two daughters were born within a year of each other. (They are the same age for three days.) Two more followed very soon after that. Jason worked at the Art Center in Fort Smith for a while, taught a course or two at UAFS, and somehow they stayed afloat. In about five years, Jason decided that he wanted to try to make it strictly on his painting. It was at this point that the term “starving artist” began to pop into our consciousness. Oh, they made it, but most of the time just barely. Paint-outs all over the country, commissions, teaching seminars – any way and every way to keep their noses above water. And, of course, the bad thing about being a painter is that a) the income is not guaranteed, and b) it is not on any kind of a regular schedule. Trying to stay on a budget was well-nigh impossible for Rebekah. Occasionally we would loan them money against prize money that Jason had earned, but which was slow in arriving. Add to that the fact that Jason was on the road much of the time, which was stressful both for him and for Rebekah. I have seen it up close, and I assure you that it is not an easy way to make a living. You just hope and pray that the artist’s health and his wife’s sanity hold out. So far they have. (Those of you whose job it is to actually send out the prize money, please be prompt. Somewhere out there could be a father-in-law who is underwriting your award, and artists have to pay the light bill just like everyone else.) Things have gotten somewhat better in recent years, but it was quite “interesting” for a while, to say the least.

So, moving back to my education as a father-in-law: I needed to learn something about art, so I figured our family’s resident artist was the best place to learn. The first thing he taught me was not to be afraid to dislike one painting and to like another. That sounds simplistic, but you artsy folks might be amazed how intimidating it is for a landlubber like me to utter, for example, “I don’t think I care for van Gogh.” Still, Jason assured me it was OK not to like his work, so I hitched up my britches, stuck out my chest, and said it a little louder: “I don’t like van Gogh!” It felt pretty good, actually – sort of therapeutic. I, Mark Green, grandson of a Depression dirt farmer, have a firm opinion about something in the world of painting. I am somebody! Of course, then I had to come up with a positive opinion. “I do like much of Monet’s work, and I really like Rembrandt.” Believe it or not, even as hidebound and reactionary as I am, I do like a significant portion of abstract art.

I had nudged the bare tip of my nose above the surface of the art-lover’s pond. But why did I like Monet, and why did I not like van Gogh? Well, there you had me: I did not have the foggiest idea. So, Professor Sacran took me in hand and began to feed me little tidbits about what makes this a good painting and what makes that a bad painting. I learned, for example, that just because I say I do not like a painting does not mean that I am saying that it is a bad painting. It might be a great work, but simply one that does not appeal to me for whatever reason. In fact, he informed me (much to my dismay at the time) that van Gogh actually was a very skilled painter. That rocked me back on my heels for moment, but I rose heroically to the occasion: “I don’t care if he is great, I still don’t like him.” That really felt good.

Now began my training in earnest. Periodically I would visit Jason’s studio (which is in the small house where my grandparents lived, under the shadow of Mount Magazine, the tallest point in mid-North America). I would say that I liked this painting and did not like that one – right to his face. And he just smiled. I even developed the temerity to tell him that a particular painting of his was not finished and that he needed to go a little further with it. Jason was very gracious and patient and would act like my opinions actually carried some weight (age does have its privileges). And finally I arrived. I got to the point where I could look at one of his new paintings and say, “I really like this one because . . . ,” and have a valid reason.

I am not an art connoisseur, and never will be. I do not have the time to spend on such a project nor the inclination to spend it. At least, however, through the kindness and patience of the father of four of my eighteen grandchildren, I have reached the point where I can confidently say that I have a clue. I do not know all the answers, but at least I can ask a few intelligent questions.

One thing I have learned about painters: evidently the most important thing you can do to become famous is to die. Death somehow seems to improve a painter’s works exponentially. Now, the walls of my house are literally papered with genuine Sacrans (most of which I picked up at fire-sale prices through my father-in-law connection). But I am 64 years old, and I am not eager to get rid of my son-in-law just to jack up the prices of my art collection. I certainly hope that my daughter is not a widow within my lifetime. So, if I am going to make any sort of a profit from all these paintings before I kick the bucket, the rest of you folks are going to have to start buying them pretty soon in large quantities. Supply and demand, you know. All you supply-stokers out there, let’s get moving! I am not getting any younger. (Besides, this guy is really good; and you have that as the official opinion of a quasi-educated art-loving father-in-law.)

+++

Folks, laying levity aside for a moment, much of what I have said here concerning Jason is just as true of a multitude of aspiring young painters across the land. Theirs is not an easy lot. Even though some would term it foolishness, it does take a great deal of courage to launch out on a career of painting with no guarantees whatsoever of success. Where family responsibilities are attached, it doubles the risk – and the stress. Please give some consideration to purchasing a work by one of them. Who knows, you may be buying a canvas by the next Picasso. But even if he does not scale that lofty height, at least you would be doing a good deed in helping one of those whose goal is to bring visual beauty into our lives.

30×24, oil on linen panel,

Collection of Artist

24″ x 20″, oil on linen panel

Private Collection

18″ x 24″, oil on linen panel

Private Collection

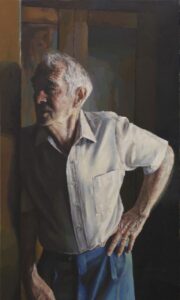

Private Collection (Portrait of “Grandpa” Logan Green)

It has been a real pleasure getting to know my in-laws, the Greens, over the last thirteen years of my life. From the very go it seemed that I was destined to be a part of the family as they took me in and made me feel welcome from the start. In fact some of them have even become subjects of my paintings, especially, “Grandpa” the patriarch of the Green family. I would say for a time he was somewhat of a muse for me, having painted upwards of a dozen studies and significant paintings of him. His son, my father-in-law, Mark Green, has recently become a subject of a life painting since retiring from his job. He visits me at my studio sometimes and we talk shop and solve world problems. This is where the idea for this article came about. He asked if he could write an article about or for me since he had the time now that he’d retired. I, of course, replied in the affirmative, and he began throwing out possible topics. At some point I asked what he thought of me, as an artist, coming into his family and taking his daughter. I told him, I’d be curious to know what his thoughts were over the years in whatever way our interaction has played out thus far. Thank you for your story, Pappy (Mark).